Class of Hope

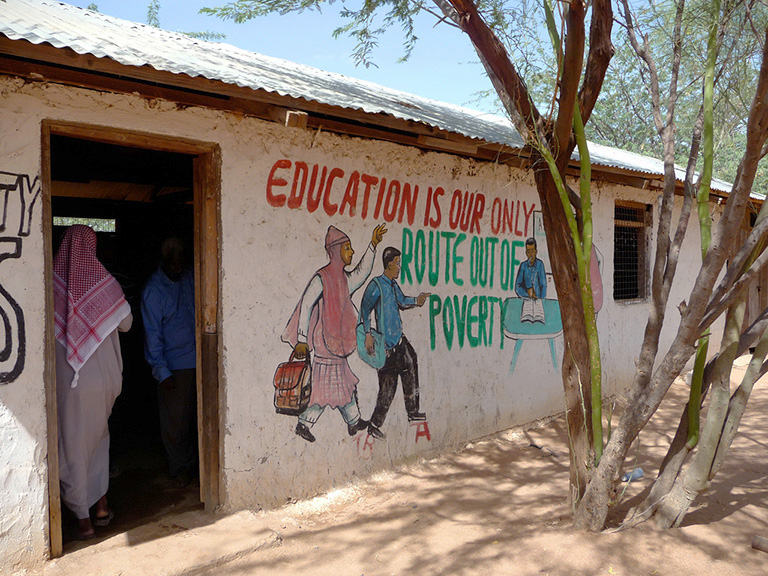

Vast, dry, dusty; from the air, the sprawling Dadaab refugee camp in north-eastern Kenya is a study in desiccated ochre, an enormous desert lichen of makeshift shelters, tents and many people.

Most are Somalis fleeing decades of violence and now sheltered in a country suffering its own woes. The first refugees arrived in the early 1960s. Today, Dabaab has swollen to almost half a million people in what is said to be the largest refugee camp in the world.

Almost 40 percent of Dadaab is of school age and of these, almost half or around 50,000 children receive no formalized education. The camp does have teachers but what they have in dedication, they almost always lack in education themselves. About 90 percent are untrained with no secondary school education and are trying to do their best for their own very large classes – almost 100 enthused students on average.

Dadaab’s teachers and students are young, eager to learn and needing help.

UBC’s Faculty of Education, along with several UBC alumni, plan to narrow those odds by ‘teaching the teachers’ on the premise that a recognized teacher-education diploma program will have a lasting and far-reaching effect from within.

With $4.5 million in funding from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), UBC has partnered with York University and three Kenyan institutions – Kenyatta University, Moi University and the African Virtual University – to form the Borderless Higher Education for Refugees (BHER) project. Moi University and UBC are partnering to offer the Dabaab Diploma in Secondary Teacher Education initiative.

In turn, York University and Kenyatta University are partnering to offer a diploma in Primary Teacher Education.

This is the first time, worldwide, that a refugee camp is being offered tertiary education, shifting the emphases from safety, food and healthcare to now include hope, transformation and professional development.

“Our hope is that we can actually enhance the education of children and youth in the camp so we can keep them in school,” says Rita Irwin, UBC alumna and associate dean of Teacher Education: “We can provide the teachers with resources that can help them navigate the difficult circumstances that they are in.”

“In some cases, they may even be able to ‘ladder’ themselves into other opportunities outside the camp; whether it’s moving to other countries or in the best possible circumstances, back to Somalia should it return to a peaceful state. They would be able to go back to their country and make a difference right away.”

Set to launch in August, the two-year program expects to train 80 teacher candidates this year and if the funding and donations allow, another 80-strong intake the following year. UBC faculty and alumni will assist, either online or in person. Much of this course development has been voluntary. All over the campus, Irwin says people are pitching in, right up to the Board of Governors:

“I think that our faculty members have really risen to the challenge. Many people were taking this on as a part of their service to the university, the larger university as a whole.” For example, when the Board of Governors was approached, it immediately offered to forego tuition and fees as a way to support this humanitarian effort.”

To date, the UBC alumni involved in the Dadaab project include Dr. George Belliveau, Bruce Gurney, Dr. Kedrick James, Dr. Elizabeth Jordan, Joanne Melville, Dr. Cynthia Nicol and Susan Thompson. Other volunteers include Dr. Lisa Loutzenheiser, Dr. Karen Meyer, Dr. Theresa Rogers and Dr. Marina Milner-Bolotin.

In her blog Thoughts on Science & Math Education, Milner-Bolotin writes that “despite the difficulty of travel, an emotional and cognitive overload while there and relatively difficult conditions (compared to what we are used to), visiting the camp was a very powerful experience for me.”

“On one hand, seeing the conditions the people in the camp live in was difficult. However, on the other hand, it was very inspirational to see how much these students yearn education and how much they value this opportunity.”

Irwin says the values gained outweigh any costs:

“This really is not ‘revenue generation’, it truly is a humanitarian effort on behalf of our faculty and the whole university. Everybody is using their creativity to think, ‘How can we best support this group of students and do so in a way that’s cost effective but is also meaningful for everyone?’ I think it’s something we should all be proud of.”

These efforts are being noticed beyond UBC and Kenya.

“There’s African awareness,” says Dr. Samson Nashon, project contact and deputy head of the Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy, UBC. “Students from Africa, the Middle East, they know about this project and every time they ask how it’s progressing and that’s very important to them, to feel that they are connected to the project.”

Read more about

Alumni EngagementRead more Alumni Engagement stories:

This story also illustrates our commitment to:

Community Engagement International Engagement Outstanding Work EnvironmentRelated Content

“This really is not ‘revenue generation’, it truly is a humanitarian effort on behalf of our faculty and the whole university."

Campus

Vancouver